Stingless bee

Stingless bees (SB), sometimes called stingless honey bees or simply meliponines, are a large group of bees (from about 462 to 552 described species),[1][2] comprising the tribe Meliponini[3][4] (or subtribe Meliponina according to other authors).[5] They belong in the family Apidae (subfamily Apinae), and are closely related to common honey bees (HB, tribe Apini), orchid bees (tribe Euglossini), and bumblebees (tribe Bombini). These four bee tribes belong to the corbiculate bees monophyletic group.[6][7] Meliponines have stingers, but they are highly reduced and cannot be used for defense, though these bees exhibit other defensive behaviors and mechanisms.[8][9] Meliponines are not the only type of bee incapable of stinging: all male bees and many female bees of several other families, such as Andrenidae and Megachilidae (tribe Dioxyini), also cannot sting.[10]

Some stingless bees have powerful mandibles and can inflict painful bites.[11][12] Some species can present large mandibular glands for the secretion of caustic defense substances, secrete unpleasant smells or use sticky materials to immobilise enemies.[13][14]

The main honey-producing bees of this group generally belong to the genera Scaptotrigona, Tetragonisca, Melipona and Austroplebeia, although there are other genera containing species that produce some usable honey. They are farmed in meliponiculture in the same way that European honey bees (genus Apis) are cultivated in apiculture.

Throughout Mesoamerica, the Mayans have engaged in extensive meliponiculture on a large scale since before the arrival of Columbus. Meliponiculture played a significant role in Maya society, influencing their social, economic, and religious activities. The practice of maintaining stingless bees in man-made structures is prevalent across the Americas, with notable instances in countries such as Brazil, Peru, and Mexico.[15][16]

Geographical distribution

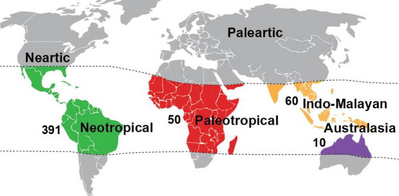

[edit]Stingless bees can be found in most tropical or subtropical regions of the world, such as the African continent (Afrotropical region), Southeast Asia and Australia (Indo-Malayan and Australasian region), and tropical America (Neotropical region).[17][18][19][20]

The majority of native eusocial bees of Central and South America are SB, although only a few of them produce honey on a scale such that they are farmed by humans.[21][22] The Neotropics, with approximately 426 species, boast the highest abundance and species richness, ranging from Cuba and Mexico in the north to Argentina in the south.[18]

They are also quite diverse in Africa, including Madagascar,[23] and are farmed there also. Around 36 species exist on the continent. The equatorial regions harbor the greatest diversity, with the Sahara Desert acting as a natural barrier to the north. The range extends southward to South Africa and southern Madagascar, with most African species inhabiting tropical forests or both tropical forests and savannahs.[18]

Meliponine honey is prized as a medicine in many African communities, as well as in South America. Some cultures use SB honey against digestive, respiratory, ocular and reproductive problems, although more research is needed to disclose evidence that supports these practices.[9][24][25]

In Asia and Australia, approximately 90 species of stingless bees span from India in the west to the Solomon Islands in the east, and from Nepal, China (Yunnan, Hainan), and Taiwan in the north to Australia in the south.

Origin and dispersion

[edit]Phylogenetic analyses reveal three distinct groups in the evolutionary history of Meliponini: the Afrotropical, the Indo-Malay/Australasia, and the Neotropical lineages. The evolutionary origin of the Meliponini is Neotropical. Studies observing contemporary species richness show that it remains highest in the Neotropics.[26]

The hypothesis proposes the potential dispersion of stingless bees from what is now North America. According to this scenario, these bees would have then traveled to Asia by crossing the Bering Strait (Beringia route) and reached Europe through Greenland (Thulean route).[27][26][28][29]

Evolution and phylogeny

[edit]Meliponines form a clade within the corbiculate bees, characterized by unique pollen-carrying structures known as corbiculae (pollen baskets) located on their hind legs. This group also includes other three tribes: honey bees (Apini), bumble bees (Bombini), and orchid bees (Euglossini). The concept of higher eusociality, defined by the presence of distinct queen and worker castes and characterized by features such as perennial colony lifestyles and extensive food sharing among adults, is particularly relevant in understanding the social structure of these tribes. Both Meliponini and Apini tribes are considered higher eusocial, while Bombini is considered to be primitively eusocial.[30]

The phylogenetic relationships among the four tribes of corbiculate bees have been a topic of considerable debate within the scientific community. Two primary questions arise: the relationship of stingless bees to honey bees and bumble bees, and whether their eusocial behavior evolved independently or from a common ancestor. Morphological and behavioral studies have suggested that Meliponini and Apini are sister groups, indicating a single origin of higher eusociality. In contrast, molecular studies often support a relationship between Meliponini and Bombini, proposing independent origins of higher eusociality in both Apini and Meliponini.[30]

A morphological, behavioral, and molecular data analysis provided strong support for the latter hypothesis of dual origins of higher eusociality. Subsequent research has reinforced the idea that stingless bees and honey bees evolved their eusocial lifestyles independently, resulting in distinct adaptive strategies for colony reproduction, brood rearing, foraging communication, and colony defense. This divergence helps explain the varied ecological and social solutions developed by these two groups of bees, such as foraging communication, colony defense/reproduction and brood rearing.[30][31]

| Anthophila (bees) |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Fossil history

[edit]The fossil record for stingless bees is notably robust compared to that of many other bee groups, with twelve extinct species currently identified. Fossils of these bees are primarily found in amber and copal, where excellent preservation typically occurs. This favorable fossilization process may be attributed to the behaviors of stingless bees, which collect significant amounts of tree resin for building nests and defense, increasing the likelihood of entrapment.[32]

Despite this relatively good fossil record, the evolutionary history of stingless bees remains poorly understood, particularly regarding their widespread distribution across various ecological niches around the globe. The oldest known fossil stingless bee is Cretotrigona prisca, a small worker bee approximately 5 mm in body length, discovered in New Jersey amber. This species is believed to have existed during the Late Cretaceous period, around 65–70 million years ago, marking it as the oldest confirmed fossil of an apid bee and the earliest fossil evidence of a eusocial bee. C. prisca exhibits striking similarities to extant stingless bees, indicating that the evolutionary lineage of meliponines may date back to this period.[32]

Some researchers suggest that stingless bees likely evolved in the Late Cretaceous, approximately 70–87 million years ago.[32][33][34] According to recent studies, corbiculate bees, which include stingless bees, are thought to have appeared around 84–87 million years ago, further supporting the notion of their evolution during this dynamic period in Earth's history.[32][35][36]

Behaviour, biology and ecology

[edit]Overview

[edit]Meliponines, considered highly eusocial insects, exhibit a remarkable caste division. The colonies typically consist of a queen, workers, and sometimes male drones.[37] The queen is responsible for reproduction, while the workers perform various tasks such as foraging, nursing, and defending the colony. Individuals work together with a well-defined division of labor for the overall benefit.[38]

Stingless bees are valuable pollinators and contribute to ecosystem health by producing essential products. These insects collect and store honey, pollen, resin, propolis, and cerumen. Honey serves as their primary carbohydrate source, while pollen provides essential proteins. Resin, propolis, and cerumen are used in nest construction and maintenance.[39][40]

Nesting behavior varies among species and may involve hollow tree trunks, external hives, the soil, termite nest or even urban structures. This adaptability underscores their resilience and ability to coexist with human activities.[41]

Castes

[edit]Workers

[edit]In a SB colony, workers constitute the predominant segment of the population, serving as the colony's primary workforce. They undertake a multitude of responsibilities crucial for the colony's well-being, including defense, cleaning, handling building materials, and the collection and processing of food. Recognizable by the corbicula - a distinctive structure on their hind legs resembling a small basket - workers efficiently carry pollen, resin, clay, and other materials gathered from the environment. Given their abundance and unique physical feature, workers play a central role in sustaining the colony.[42][43][44]

Queens

[edit]The principal egg layer in SB colonies is the queen, distinguished from the workers by differences in both size and shape. Stingless bee queens - except in the case of the Melipona genus, where queens and workers receive similar amounts of food and thus exhibit similar sizes - are generally larger and weigh more than workers (approximately 2–6 times). Post-mating, meliponine queens undergo physogastry, developing a distended abdomen. This physical transformation sets them apart from honey bee queens, and even Melipona queens can be easily identified by their enlarged abdomen after mating.[37][45][46]

Stingless bee colonies typically follow a monogynous structure, featuring a single egg-laying queen. An exception is noted in Melipona bicolor colonies, which are often polygynous (large populations may have as many as 5 physogastric queens simultaneously involved in oviposition).[46][38][47] Depending on the species, queens can lay varying quantities of eggs daily, ranging from a dozen (e.g., Plebeia julianii) to several hundred (e.g., Trigona recursa). While information on queen lifespans is limited, available data suggest that queens generally outlive workers, with lifespans usually falling between 1 and 3 years, although some queens may live up to 7 years.[46][47]

The laying queen assumes the crucial role of producing eggs that give rise to all castes within the colony. Additionally, she plays a pivotal role in organizing the colony, overseeing a complex communication system primarily reliant on the use of pheromones.[45]

Males (drones)

[edit]The primary function of males, or drones, is to mate with queens, performing limited tasks within the nest and leaving at around 2–3 weeks old, never to return. The production of males can vary, occurring continuously, sparsely or in large spurts when numerous drones emerge from brood combs for brief periods. Identifying a male can be challenging due to its similar body size to workers, but distinctive features such as the absence of a corbicula, larger eyes, slightly smaller mandibles, slightly longer and v-shaped antennae, and often a lighter face color distinguish them. Clusters of males, numbering in the hundreds, can be observed outside colonies, awaiting the opportunity to mate with virgin queens.[43][48][49]

Males in a stingless bee colony, either produced mainly by the laying queen or primarily by the workers, play an important role in reproduction. Workers can produce males by laying unfertilized eggs, enabled by the haplodiploidy system, where males are haploid, having only one set of chromosomes, while workers are diploid and incapable of producing female eggs due to their inability to mate. This sex determination system is common to all hymenopterans.[50]

Soldiers

[edit]While the existence of a soldier caste is well known in ants and termites, the phenomenon was unknown among bees until 2012, when some stingless bees were found to have a similar caste of defensive specialists that help guard the nest entrance against intruders.[51] To date, at least 10 species have been documented to possess such "soldiers", including Tetragonisca angustula, T. fiebrigi, and Frieseomelitta longipes, with the guards not only larger, but also sometimes a different color from ordinary workers.[52][53]

Division of labour

[edit]When the young worker bees emerge from their cells, they tend to initially remain inside the hive, performing different jobs. As workers age, they become guards or foragers. Unlike the larvae of honey bees and many social wasps, meliponine larvae are not actively fed by adults (progressive provisioning). Pollen and nectar are placed in a cell, within which an egg is laid, and the cell is sealed until the adult bee emerges after pupation (mass provisioning).

At any one time, hives can contain from 300 to more than 100,000 workers (with some authors claiming to calculate more than 150,000 workers, but with no methodology explanation), depending on species.[54]

Products and materials

[edit]The industrious nature of stingless bees extends to their building activities. Unlike honey bees, they do not use pure wax for construction but combine it with resin to create cerumen, a material employed in constructing nest structures such as brood cells, food pots, and the protective involucrum. Wax is secreted by young bees through glands located on the top of their abdomen and this mixture not only provides structural strength but also offers antimicrobial properties, inhibiting the growth of fungi and bacteria. The creation of batumen involves combining cerumen with additional resin, mud, plant material, and sometimes even animal feces. Batumen, a stronger material, forms protective layers covering the walls of the nesting space, ensuring the safety of the colony.[55][56][57][58]

On the other hand, clay, sourced from the wild and exhibiting diverse colors based on its mineral origin, serves as another essential raw material for SB. While it can be used in its pure form, it is more common to combine clay with vegetable resins to produce geopropolis. The inclusion of clay in this mixture enhances the durability and structural integrity of the resulting substance.[55][56][57][58]

Vegetable resin, gathered from a variety of plant species in the wild, is an essential raw material brought back to the hive. Stored in small, sticky clumps in peripheral areas of the colony, it is often mistakenly treated as a synonym for propolis. However, in beekeeping terminology, propolis refers to a mixture of resin, wax, enzymes, and possibly other substances. Stingless bees go beyond the classic propolis by producing various derivatives from resins and wax, sometimes using pure resins for sealing or defense, a behavior not observed in Apis bees. Understanding these distinctions is vital for effective production and value addition to the meliponiculture activity.[55][56][57][58]

Honey, a prized product of bee colonies, is crafted through the processing of nectars, honeydews, and fruit juices by worker bees. They store these collected substances in an extension of their gut called a crop. Back at the hive, the bees ripen or dehydrate the nectar droplets by spinning them inside their mouthparts until honey is formed. Ripening concentrates the nectar and increases the sugar content, though it is not nearly as concentrated as the honey from Apis mellifera. Stored in food pots, meliponines' honey is often referred to as pot-honey due to its distinctive storage method. Stingless bee honeys differ from A. mellifera honey in terms of color, texture, and flavor, being more liquid with a higher water content. Rich in minerals, amino acids, and flavonoid compounds, the composition of honey varies among colonies of the same species, influenced by factors such as season, habitat, and collected resources.[55][56][57][58]

Special methods are being developed to harvest moderate amounts of honey from stingless bees in these areas without causing harm. For honey production, the bees need to be kept in a box specially designed to make the honey stores accessible without damaging the rest of the nest structure. Some recent box designs for honey production provide a separate compartment for the honey stores so the honey pots can be removed without spilling honey into other areas of the nest. Unlike a hive of commercial honeybees, which can produce 75 kg (165 lbs) of honey a year, a hive of Australian stingless bees produces less than 1 kg (2 lbs). Stingless bee honey has a distinctive "bush" taste—a mix of sweet and sour with a hint of fruit.[59][60][61] The taste comes from plant resins—which the bees use to build their hives and honey pots—and varies at different times of year depending on the flowers and trees visited.

In 2020 researchers at the University of Queensland found that some species of stingless bee in Australia, Malaysia, and Brazil produce honey that has trehalulose—a sugar with an unusually low glycaemic index (GI) compared to that of glucose and fructose, the main sugars composing conventional honey.[62][63] Such low glycaemic index honey is beneficial for humans because its consumption does not cause blood sugar to spike, forcing the body to make more insulin in response. Honey with trehalulose is also beneficial as it this sugar cannot nourish the lactic acid-producing bacteria that cause tooth decay. The university's findings supported the long-standing claims of Indigenous Australian people that native honey is beneficial to human health.[63][64] This type of honey is scientifically supported as providing therapeutic value to humans as well.[63][65][66][67][68]

Nest

[edit]

Stingless bees, as a collective group, display remarkable adaptability to diverse nesting sites. They can be found in exposed nests in trees, from living in ant and termite nests above and below ground to cavities in trees, trunks, branches, rocks, or even human constructions.[69]

Many beekeepers keep the bees in their original log hive or transfer them to a wooden box, as this makes controlling the hive easier. Some beekeepers put them in bamboos, flowerpots, coconut shells, and other recycling containers such as a water jug, a broken guitar, and other safe and closed containers.[70][71][72]

Exposed nests

[edit]

Notably, certain species, such as the African Dactylurina, construct hanging nests from the undersides of large branches for protection against adverse weather conditions. Additionally, some American Trigona species, including T. corvina, T. spinipes, and T. nigerrima, as well as Tetragonisca weyrauchi, build fully exposed nests.[69]

Ground nests

[edit]

A significant minority of meliponine species, belonging to genera like Camargoia, Geotrigona, Melipona, Mourella, Nogueirapis, Paratrigona, Partamona, Schwarziana, and others, opt for ground nests. These species take advantage of cavities in the ground, often utilizing abandoned nests of ants, termites, or rodents. Unlike some other cavity-nesting bees, stingless bees in this category do not excavate their own cavities but may enlarge existing ones.[69]

Termite and ant shared nests

[edit]Numerous stingless bee species have evolved to coexist with termites. They inhabit parts of ant or termite nests, both above and below ground. These nests are often associated with various ant species, such as Azteca, Camponotus, or Crematogaster, and termite species like Nasutitermes, Constrictotermes, Macrotermes, Microcerotermes, Odontotermes, or Pseudocanthotermes. This strategy allows SB to utilize pre-existing cavities without the need for extensive excavation.[69]

Cavity nests

[edit]The majority of stingless bees favor nesting in pre-existing cavities within tree trunks or branches. Nesting heights vary, with some colonies positioned close to the ground, typically below 5 meters, while others, like Trigona and Oxytrigona, may nest at higher elevations, ranging from 10 to 25 meters. Some species, such as Melipona nigra, exhibit unique nesting habits at the foot of a tree in root cavities or between roots. The choice of nesting height has implications for predation pressure and the microclimate experienced by the colony.[69]

The majority of stingless bee species exhibit a non-specific preference when it comes to selecting tree species for nesting. Instead, they opportunistically exploit whatever nesting sites are available This adaptability underscores the versatility of SB in adapting to various arboreal environments. Furthermore, cavity-nesting species can opportunistically utilize human constructions, nesting under roofs, in hollow spaces in walls, electricity boxes, or even metal tubes. In few cases, specific tree species, like Caryocar brasiliense, may be preferred by certain stingless bee species (Melipona quadrifasciata), illustrating a degree of selectivity in nesting choices among different groups.[69][73]

Entrances

[edit]Entrance tubes showcase a spectrum of characteristics, from being hard and brittle to soft and flexible. In many situations, the portion near the opening remains soft and flexible, aiding workers in sealing the entrance during the night. The tubes may also feature perforations and a coating of resin droplets, adding to the complexity of their design.[74]

The entrances serve as essential visual landmarks for returning bees, and they are often the first structures constructed at a new nest site. The diversity in entrance size influences foraging traffic, with larger entrances facilitating smoother traffic but potentially necessitating more entrance guards to ensure adequate defense.[74]

Some Partamona species exhibit a distinctive entrance architecture, where workers of P. helleri construct a large outer mud entrance leading to a smaller adjacent entrance. This unique design enables foragers to enter with high speed, bouncing off the ceiling of the outer entrance towards the smaller inner entrance. The peculiar appearance of this entrance has led to local names such as "toad mouth", highlighting the intriguing adaptations found in stingless bee nest entrances.[74]

- Different species nest entrances in Brazilian stingless bees

Brood cell arrangement

[edit]Stingless bee colonies exhibit a diversity of construction patterns of brood cells, primarily composed of soft cerumen, a mixture of wax and resin. Each crafted cell is designed to rear a single individual bee, emphasizing the precision and efficiency of their nest architecture.[74]

The quantity of brood cells within a nest displays significant variation across different stingless bee species. Nest size can range from a few brood cells, as observed in the Asian Lisotrigona carpenteri, to remarkably expansive colonies with over 80,000 brood cells, particularly in some American Trigona species.[74]

Meliponine colonies exhibit diverse brood cell arrangements, primarily categorized into three main types: horizontal combs, vertical combs, and clustered cells. Despite these primary types, variations and intermediate forms are prevalent, contributing to the flexibility of nest structures.[74][75]

The first type involves horizontal combs, often characterized by a spiral pattern or layers of cells. The presence of spirals may not be consistent within a species, varying among colonies or even within the same colony. Some species, such as Melipona, Plebeia, Plebeina, Nannotrigona, Trigona, and Tetragona, may occasionally build spirals alongside other comb structures, as observed in Oxytrigona mellicolor. As space diminishes for upward construction, workers initiate the creation of a new comb at the bottom of the brood chamber. This innovative approach optimizes the available space when emerging bees vacate older, lower brood combs.[74]

The second prevalent brood cell arrangement involves clusters of cells held together with thin cerumen connections. This clustered style is observed in various distantly related genera, such as the American Trigonisca, Frieseomelitta, Leurotrigona, the Australian Austroplebeia, and the African Hypotrigona. This arrangement is particularly useful for colonies in irregular cavities unsuitable for traditional comb building.[74]

The construction of vertical combs is a distinctive trait found in only two stingless bee species: the African Dactylurina and the American Scaura longula. This vertical arrangement sets these species apart from the more commonly observed horizontal comb structures in other stingless bee genera.[74]

Brood rearing

[edit]Stingless bee brood rearing is a sophisticated and intricately coordinated process involving various tasks performed by worker bees, closely synchronized with the queen's activities. The sequence begins with the completion of a new brood cell, marking the initiation of mass provisioning.[76]

Upon finishing a brood cell, several workers engage in mass provisioning, regurgitating larval food into the cell. This collective effort is swiftly followed by the queen laying her egg on top of the provided larval food. The immediate sealing of the cell ensues shortly afterward, culminating this important phase of the brood rearing process.[76]

The practice of mass provisioning, oviposition, and cell sealing is considered an ancestral trait, shared with solitary wasps and bees. However, in the context of stingless bees, these actions represent distinct stages of a highly integrated social process. Notably, the queen plays a central role in orchestrating these activities, acting as a pacemaker for the entire colony.[76]

This process diverges significantly from brood rearing in Apis spp. In honeybee colonies, queens lay eggs into reusable empty cells, which are then progressively provisioned over several days before final sealing. The contrasting approaches in brood rearing highlight the unique social dynamics and adaptations within stingless bee colonies.[76]

Swarming

[edit]Stingless bees and honey bees, despite encountering a common challenge in establishing daughter colonies, employ contrasting strategies. There are three key differences: reproductive status and age of the queen that leaves the nest, temporal aspects of colony foundation, and communication processes for nest site selection.[77]

In HB (Apis mellifera), the mother queen, accompanied by a swarm of numerous workers, embarks on relocation to a new home once replacement queens have been reared. Conversely, in SB (meliponines), the departure is orchestrated by the unmated ("virgin") queen, leaving the mother queen in the original nest. Mated stingless bee cannot leave the hive due to damaged wings and increased abdominal size post-mating (physogastrism). The queen's weight in species like Scaptotrigona postica increases, for example, about 250%.[77][78]

Unlike honey bees, stingless bee colonies are unable to perform absconding - a term denoting the abandonment of the nest and migration to a new location - making them reliant on alternative strategies to cope with challenges. Meliponines progressive found new colonies without abandonning their nest abruptly.[77]

These are the stages of stingless bees swarming:[77]

- Reconnaissance and preparation: Scouts inspect potential new nest sites for suitability, considering factors such as cavity size, entrance characteristics, and potential threats. The criteria for determining suitability remain largely unexplored. Some colonies engage in simultaneous preparation of multiple cavities before making a final decision and some others make the initial reconnaissance but do not move into the cavity;

- Transport of building material and food: workers seal cracks in the chosen cavity using materials like resin, batumen, or mud. They construct an entrance tube, possibly serving as a visual beacon for nestmate workers. Early food pots are built and filled with honey, requiring a growing number of workers to transport cerumen and honey from the mother nest.

- Progressive establishment and social link: the mother and daughter colony maintain a social link through workers traveling between the two nests. The duration of this link varies among species, ranging from a few days to several months. Stingless bee colonies display a preference for cavities previously used by other colonies, containing remnants of building material and nest structures.

- Arrival of the queen: after initial preparations, an unmated queen, accompanied by additional workers, arrives at the new nest site.

- Drone arrival: males (drones) aggregate outside the newly established nest. They often arrive shortly after swarming initiation, even before the completion of nest structures. Males can be observed near the entrance, awaiting further events.

- Mating flight: males in aggregations do not enter the colony but await the queen's emergence for a mating flight. Although rarely observed, it is assumed that unmated stingless bee queens embark on a single mating flight, utilizing acquired sperm for the entirety of their reproductive life.

Natural enemies

[edit]In meliponiculture, beekeepers need to be aware of the presence of animals that can harm stingless bee colonies. There are several potential enemies, but the most damaging ones to meliponaries are listed below.[79]

Invertebrates

[edit]

Phorid flies in the genus Pseudohypocera pose a significant threat to stingless bee colonies, causing problems for beekeepers. These parasites lay eggs in open cells of pollen and honey, leading to potential extinction if not addressed. Early detection is crucial for manual removal or using vinegar traps. It's important never to leave an infested box unattended to prevent the cycle from restarting and avoid contaminating other colonies. Careful handling of food jars, especially during swarms transfers, is essential. Prompt removal of broken jars, sealing gaps with wax or tape, and maintaining vigilance during the rainy season for heightened phorid activity are recommended. Combatting these flies usually is a priority, particularly during increased reproductive periods.[80][81][82]

Termites usually do not attack bees or their food pots. However, they can cause damage to the structure of hive boxes as there are many xylophagous species. While termites do not usually pose major problems for beekeepers, they should still be monitored closely.[83][84]

Ants are attracted to bee colonies by the smell of food. To prevent ant attacks, it's important to handle the hive boxes carefully and avoid exposing jars of pollen and honey. Although rare, when attacks do occur, there are intense conflicts between ants and bees. Stingless bees usually manage to defend themselves, but the damage to the bee population can be significant. To prevent ant infestations in meliponaries with individual supports, a useful strategy is to impregnate the box supports with burnt oil.[85][86]

Another group of enemy flies are the black soldier flies (Hermetia illucens). They lay their eggs in crevices of boxes and can extend the tip of their abdomen during laying, facilitating access to the inside of the hive. Larvae of this species feed on pollen, feces, and other materials found in colonies. In general, healthy bee colonies can coexist peacefully with soldier flies. However, in areas where these insects are prevalent, beekeepers must remain vigilant and protect the gaps in the colonies to prevent potential issues.[87]

Cleptobiosis, also known as cleptoparasitism, is a behaviour observed in various species of stingless bees, with over 30 identified species engaging in nest attacks, including honey bee nests. This behaviour serves the purpose of either resource theft or usurping the nest by swarming into an already occupied cavity and these bees are called robber bees. The Neotropical genus Lestrimelitta and the African genus Cleptotrigona represent bees with an obligate cleptobiotic lifestyle since they do not visit flowers for nectar or pollen.

Furthermore, other species such as Melipona fuliginosa, Oxytrigona tataira, Trigona hyalinata, T. spinipes, and Tetragona clavipes are reported to have comparable habits of pillaging and invading, which emphasises the variety of strategies employed by stingless bees in acquiring resources.

Other enemies include: jumping spiders (Salticidae), moths, assassin bugs (Reduviidae), beetles, parasitoid wasps, predatory mites (Amblyseius), mantises (Mantodea), robber flies (Asilidae), etc.[88]

Vertebrates

[edit]Human activities pose the most significant threat to stingless bees, whether through honey and nest removal, habitat destruction, pesticide use or introduction of non-native competitors. Large-scale environmental alterations, particularly the conversion of natural habitats into urban or intensively farmed land, are the most dramatic threats leading to habitat loss, reduced nest densities, and species disappearance.[89]

Primates, including chimpanzees, gorillas, baboons, and various monkey species, are known to threaten stingless bee colonies. Elephants, honey badgers, sun bears, spectacled bears, anteaters, hog-nosed skunks, armadillos, tayras, eyra cats, kinkajous, grisons, and coyotes are among the mammals that consume or destroy stingless bee nests. Some, like the tayra and eyra cat, have specific preferences for stealing honey. Geckos, lizards, and toads also pose threats by hunting adult bees or consuming workers at nest entrances. Woodpeckers and various bird species, including bee-eaters, woodcreepers, drongos, jacamars, herons, kingbirds, flycatchers, swifts, and honeyeaters, occasionally prey on stingless bees. African honeyguides have developed a mutualism with human honey-hunters, actively guiding them to bee nests for honey extraction and then consuming leftover wax and larvae.[89]

Defense

[edit]Being tropical, stingless bees are active all year round, although they are less active in cooler weather, with some species presenting diapause.[90][91][92] Unlike other eusocial bees, they do not sting, but will defend by biting if their nest is disturbed. In addition, a few (in the genus Oxytrigona) have mandibular secretions, including formic acid, that cause painful blisters.[13][93] Despite their lack of a sting, stingless bees, being eusocial, may have very large colonies made formidable by the number of defenders.[94][95]

Stingless bees use other sophisticated defence tactics to protect their colonies and ensure their survival. One important strategy is to choose nesting habitats with fewer natural enemies to reduce the risk of attacks. In addition, they use camouflage and mimicry to blend into their surroundings or imitate other animals to avoid detection. An effective strategy is to nest near colonies that provide protection, using collective strength to defend against potential invaders.[90]

Nest entrance guards play a vital role in colony defense by actively preventing unauthorized entry through attacking intruders and releasing alarm pheromones to recruit additional defenders. It is worth noting that nest guards often carry sticky substances, such as resins and wax, in their corbiculae or mandibles. Stingless bees apply substances to attackers to immobilise them, thus thwarting potential threats to the colony. Some species (Tetragonisca angustula and Nannotrigona testaceicornis, for example) also close their nest entrances with a soft and porous layer of cerumen at night, further enhancing colony security during vulnerable periods. These intricate defence mechanisms demonstrate the adaptability and resilience of stingless bees in safeguarding their nests and resources.[90]

Role differentiation

[edit]In a simplified sense, the sex of each bee depends on the number of chromosomes it receives. Female bees have two sets of chromosomes (diploid)—one set from the queen and another from one of the male bees or drones. Drones have only one set of chromosomes (haploid), and are the result of unfertilized eggs, though inbreeding can result in diploid drones.

Unlike true honey bees, whose female bees may become workers or queens strictly depending on what kind of food they receive as larvae (queens are fed royal jelly and workers are fed pollen), the caste system in meliponines is variable, and commonly based simply on the amount of pollen consumed; larger amounts of pollen yield queens in the genus Melipona. Also, a genetic component occurs, however, and as much as 25%[96] (typically 5–14%) of the female brood may be queens. Queen cells in the former case can be distinguished from others by their larger size, as they are stocked with more pollen, but in the latter case, the cells are identical to worker cells, and scattered among the worker brood. When the new queens emerge, they typically leave to mate, and most die.[97] New nests are not established by swarms, but by a procession of workers that gradually construct a new nest at a secondary location. The nest is then joined by a newly mated queen, at which point many workers take up permanent residence and help the new queen raise her own workers. If a ruling queen is herself weak or dying, then a new queen can replace her. For Schwarziana quadripunctata, although fewer than 1% of female worker cells produce dwarf queens, they comprise six of seven queen bees, and one of five proceed to head colonies of their own. They are reproductively active, but less fecund than large queens.[97]

Interaction with humans

[edit]Pollination

[edit]

Bees play a critical role in the ecosystem, particularly in the pollination of natural vegetation. This activity is essential for the reproduction of various plant species, particularly in tropical forests where most tree species rely on insect pollination. Even in temperate climates, where wind pollination is prevalent among forest trees, many bushes and herbaceous plants, rely on bees for pollination. The significance of bees extends to arid regions, such as desertic and xeric shrublands, where bee-pollinated plants are essential for preventing erosion, supporting wildlife, and ensuring ecosystem stability.[98]

The impact of bee pollination on agriculture is substantial. In the late 1980s, certain plants were estimated to contribute between $4.6 to $18.9 billion to the U.S. economy, primarily through insect-pollinated crops. Although some bee-pollinated plants can self-pollinate in the absence of bees, the resulting crops often suffer from inbreeding depression. The quality and quantity of seeds or fruits are significantly enhanced when bees participate in the pollination process. Although estimates of crop pollination attributed to honey bees are uncertain, it is undeniable that bee pollination is a vital and economically valuable activity.[98]

Ramalho (2004) demonstrates that stingless bees amount to approximately 70% of all bees foraging on flowers in the Brazilian Tropical Atlantic Rainforest even though they represented only 7% of all bee species.[99] In a habitat in Costa Rica, stingless bees accounted for 50% of the observed foraging bees, despite representing only 16% of the recorded bee species.[100] Following this pattern, Cairns et al. (2005) found that 52% of all bees visiting flowers in Mexican habitats were meliponines.[101]

Meliponine bees play a crucial role in tropical environments due to their high population rate, morphological diversity, diverse foraging strategies, generalist foraging habits (polylecty), and flower constancy during foraging trips. Nest densities and colony sizes can result in over a million individual stingless bees inhabiting a square kilometre of tropical habitat. Due to their diverse morphology and behaviour, bees are capable of collecting pollen and nectar from a wide range of flowering plants. Key plant families are reported as most visited by meliponines: Fabaceae, Euphorbiaceae, Asteraceae and Myrtaceae.[102]

Grüter compiled some studies about twenty crops that substantially benefit from SB pollination (following table) and also lists seventy-four crops that are at least occasionally or potentially pollinated by stingless bees.[102]

Worldwide overview

[edit]Africa

[edit]Stingless bees also play a vital ecological role across Sub-Saharan Africa and Madagascar. To understand these insects on the African continent, it's important to consider the prevailing socio-economic and cultural contexts. Despite their ecological significance, the diversity, conservation, and behavior of these bees remain underexplored, particularly compared to better-studied regions such as South America and Southeast Asia. Also, honeybees were extensively researched, in contrast to native meliponines.[108][109]

Africa is home to seven biodiversity hotspots, yet the recorded bee fauna is moderate relative to the continent's size. Madagascar stands out with exceptionally high levels of endemic species, though much of the bee diversity remains undocumented.[110][108] Africa is home to aproximately 36 species of meliponines, including seven endemic to Madagascar. Most of these bees are found in equatorian regions (tropical forests and some savannahs).[111]

Factors such as habitat destruction, pesticide use, and invasive species pose significant threats to these pollinators. Furthermore, high rates of nest mortality, driven by predation and human activity, exacerbate conservation challenges. Research indicates that stingless bees in Africa face greater pressures than their counterparts in the American and Asian tropics, underlining the urgency for targeted conservation measures.[110][108]

Uganda's Bwindi Impenetrable National Park has shown the presence of at least five stingless bee species in, distributed across two genera: Meliponula and Hypotrigona.[108][109] In Madagascar, there is only one genus of stingless bees: Liotrigona.[110]

Meliponiculture, for example, is practised in Angola and Tanzania, and interest in managing stingless bees is growing in other African countries as well. [112]

Australia

[edit]Of the 1,600 species of wild bees native to Australia, about 14 are meliponines.[113] "Coot-tha", which derives from "ku-ta", is one of the Aboriginal names for "wild stingless bee honey".[114] These species bear a variety of names, including Australian native honey bees, native bees, sugar-bag bees, and sweat bees (because they land on people's skin to collect sweat).[115] The various stingless species look quite similar, with the two most common species, Tetragonula carbonaria and Austroplebeia australis, displaying the greatest variation, as the latter is smaller and less active. Both of these inhabit the area around Brisbane.[116]

As stingless bees are usually harmless to humans, they have become an increasingly attractive addition to the suburban backyard. Most meliponine beekeepers do not keep the bees for honey, but rather for the pleasure of conserving native species whose original habitat is declining due to human development. In return, the bees pollinate crops, garden flowers, and bushland during their search for nectar and pollen. While a number of beekeepers fill a small niche market for bush honey, native meliponines only produce small amounts and the structure of their hives makes the honey difficult to extract. Only in warm areas of Australia such as Queensland and northern New South Wales are favorable for these bees to produce more honey than they need for their own survival. Most bees only come out of the hive when it is above about 18°C (64°F).[117] Harvesting honey from a nest in a cooler area could weaken or even kill the nest.

Pollination

[edit]Australian farmers rely almost exclusively on the introduced western honey bee to pollinate their crops. However, native bees may be better pollinators for certain agricultural crops. Stingless bees have been shown to be valuable pollinators of tropical plants such as macadamias and mangos.[103] Their foraging may also benefit strawberries, watermelons, citrus, avocados, lychees, and many others.[103][105] Research into the use of stingless bees for crop pollination in Australia is still in its very early stages, but these bees show great potential. Studies at the University of Western Sydney have shown these bees are effective pollinators even in confined areas, such as glasshouses.[118]

Brazil

[edit]

Brazil is home to several species bees belonging to Meliponini, with more than 300 species already identified and probably more yet to be discovered and described. They vary greatly in shape, size, and habits, and 20 to 30 of these species have good potential as honey producers. Although they are still quite unknown by most people, an increasing number of beekeepers (meliponicultores, in Portuguese) have been dedicated to these bees throughout the country.[2][119] This activity has experienced significant growth since August 2004, when national laws were changed to allow native bee colonies to be freely marketed, which was previously forbidden in an unsuccessful attempt to protect these species. Nowadays the capture or destruction of existing colonies in nature is still forbidden, and only new colonies formed by the bees themselves in artificial traps can be collected from the wild.[120] Most marketed colonies are artificially produced by authorized beekeepers, through division of already existing captive colonies. Besides honey production, Brazilian stingless bees such as the jataí (Tetragonisca angustula), mandaguari (Scaptotrigona postica), and mandaçaia (Melipona quadrifasciata) serve as major pollinators of tropical plants and are considered the ecological equivalent of the honey bee.[103][105]

Also, much practical and academic work is being done about the best ways of keeping such bees, multiplying their colonies, and exploring the honey they produce.[121] Among many others, species such as jandaíra (Melipona subnitida) and true uruçu (Melipona scutellaris) in the northeast of the country, mandaçaia (Melipona quadrifasciata) and yellow uruçu (Melipona rufiventris) in the south-southeast, tiúba or jupará (Melipona interrupta) and canudo (Scaptotrigona polysticta) in the north and jataí (Tetragonisca angustula) throughout the country are increasingly kept by small, medium, and large producers. Many other species as the mandaguari (Scaptotrigona postica), the guaraipo (Melipona bicolor), marmelada (Frieseomelitta varia) and the iraí (Nannotrigona testaceicornis), to mention a few, are also reared.[122]

According to ICMBio and the Ministry of the Environment there are presently four species of Meliponini listed in the National Red List of Threatened Species in Brazil. Melipona capixaba, Melipona rufiventris, Melipona scutellaris, and Partamona littoralis all listed as Endangered (EN).[123][124]

Honey production

[edit]Although the colony population of most of these bees is much smaller than that of European bees, the productivity per bee can be quite high. Interestingly, honey production is more connected to the body size, not the colony size. The manduri (Melipona marginata), jandaíra (Melipona subnitida) and the guaraipo (M. bicolor) live in swarms of only around 300 individuals but can still produce up to 5 liters (1.3 US gallon) of honey a year under the right conditions.[125] In large bee farms, only the availability of flowers limits the honey production per colony. However, much larger numbers of beehives are required to produce amounts of honey comparable to that of European bees. Also, due to the fact of those bees storing honey in cerumen pots instead of standardized honeycombs as in the honeybee rearing makes extraction a lot more difficult and laborious.[126]

The honey from stingless bees has a higher water content, from 25% to 35%, compared to the honey from the genus Apis. This contributes to its less cloying taste but also causes it to spoil more easily. Thus, for marketing, this honey needs to be processed through desiccation, fermentation or pasteurization. In its natural state, it should be kept under refrigeration.[127]

Bees as pets

[edit]

Due to the lack of a functional stinger and characteristic nonaggressive behavior of many Brazilian species of stingless bees, they can be reared without problems in densely populated environments (residential buildings, schools, urban parks), provided enough flowers are at their disposal nearby. Some breeders (meliponicultores) can produce honey even in apartments up to the 12th floor.[128]

The mandaçaias (Melipona quadrifasciata) are extremely tame, rarely attacking humans (only when their hives are opened for honey extraction or colony division). They form small, manageable colonies of only 400–600 individuals. They are fairly large bees, up to 11 mm (7/16") in length, and as a result have better body heat control, allowing them to live in regions where temperatures can drop a little lower than 0 °C (32 °F). However, they are somewhat selective about which flowers they will visit, preferring the flora that occurs in their natural environment. They are thus difficult to keep outside their region of origin (the eastern coast of Brazil). Once very common, the mandaçaia is now rather rare in nature, mainly due to the destruction of their native forests in the of Brazil.[129][122]

Other groups of Brazilian stingless bees, genera Plebeia and Leurotrigona, are also very tame and much smaller, with one of them (Plebeia minima) reaching no more than 2.5 mm (3/32") in length, and the lambe-olhos ("lick-eyes" bee, Leurotrigona muelleri) being even smaller, at no more than 1.5 mm (3/32"). Many of these species are known as mirim (meaning 'small' in the Tupi-Guarani languages). As a result, they can be kept in very small artificial hives, thus being of interest for keepers who want them as pollinators in small glasshouses or just for the pleasure of having a 'toy' bee colony at home.[122][130][131] Being so tiny, these species produce only a very small amount of honey, typically less than 500 ml (1/2 US pint) a year, so are not interesting for commercial honey production.

Belonging to the same group, the jataí (Tetragonisca angustula), the marmelada (Frieseomelitta varia), and the moça-branca (Frieseomelitta doederleini) are intermediate in size between those very small species and the European bee. They are very adaptable species; the jataí, and can be reared in many different regions and environments, being quite common in most Brazilian cities. The jataí can bite when disturbed, but its jaws are weak, and in practice they are harmless, while the marmelada and moça-branca usually deposit propolis on their aggressors. Jataí is one of the first species to be kept by home beekeepers. Their nests can be easily identified in trees or wall cavities by the yellow wax pipe they build at the entrance, usually guarded by some soldier bees, which are stronger than regular worker bees. The marmelada and moça-branca make a little less honey, but it is denser and sweeter than most from other stingless bees and is considered very tasty.[122][132]

Central America

[edit]

The stingless bees Melipona beecheii and M. yucatanica are the primary native bees cultured in Central America, though a few other species are reported as being occasionally managed (e.g., Trigona fulviventris and Scaptotrigona mexicana).[133] They were extensively cultured by the Maya civilization for honey, and regarded as sacred. They continue to be cultivated by the modern Maya peoples, although these bees are endangered due to massive deforestation, altered agricultural practices (especially overuse of insecticides), and changing beekeeping practices with the arrival of the Africanized honey bee, which produces much greater honey crops.[72]

History

[edit]Native meliponines (M. beecheii being the most common) have been kept by the lowland Maya for thousands of years. The Yucatec Maya language name for this bee is xunan kab, meaning "(royal, noble) lady bee".[134][135] The bees were once the subject of religious ceremonies and were a symbol of the bee-god Ah-Muzen-Cab, known from the Madrid Codex.[136]

The bees were, and still are, treated as pets. Families would have one or many log-hives hanging in and around their houses. Although they are stingless, the bees do bite and can leave welts similar to a mosquito bite. The traditional way to gather bees, still favored among the locals, is find a wild hive, then the branch is cut around the hive to create a portable log, enclosing the colony. With proper maintenance, hives have been recorded as lasting over 80 years, being passed down through generations. In the archaeological record of Mesoamerica, stone discs have been found that are generally considered to be the caps of long-disintegrated logs that once housed the beehives.[136][137]

Tulum

[edit]Tulum, the site of a pre-Columbian Maya city on the Caribbean coast 130 km (81 mi) south of Cancun, has a god depicted repeatedly all over the site. Upside down, he appears as a small figure over many doorways and entrances. One of the temples, the Temple of the Descending God (Templo del Dios Descendente), stands just left of the central plaza. Speculation is that he may be the "Bee God", Ah Muzen Cab, as seen in the Madrid Codex. It is possible that this was a religious/trade center with emphasis on xunan kab, the "royal lady".[137]

Economic uses

[edit]Balché, a traditional Mesoamerican alcoholic beverage similar to mead, was made from fermented honey and the bark of the leguminous balché tree (Lonchocarpus violaceus), hence its name. It was traditionally brewed in a canoe. The drink was known to have entheogenic properties, that is, to produce mystical experiences, and was consumed in medicinal and ritual practices. Beekeepers would place the nests near the psychoactive plant Turbina corymbosa and possibly near balché trees, forcing the bees to use nectar from these plants to make their honey. Additionally, brewers would add extracts of the bark of the balché tree to the honey mixture before fermentation. The resulting beverage is responsible for psychotropic effects when consumed, due to the ergoline compounds in the pollen of the T. corymbosa, the Melipona nectar gathered from the balché flowers, or the hallucinogenic compounds of the balché tree bark.[138]

Lost-wax casting, a common metalworking method typically found where the inhabitants keep bees, was also used by the Maya. The wax from Melipona is soft and easy to work, especially in the humid Maya lowland. This allowed the Maya to create smaller works of art, jewelry, and other metalsmithing that would be difficult to forge. It also makes use of the leftovers from honey extraction. If the hive was damaged beyond repair, the whole of the comb could be used, thus using all of the hive. With experienced keepers, though, only the honey pot could be removed, the honey extracted, and the wax used for casting or other purposes.[139][140]

Future

[edit]The outlook for meliponines in Mesoamerica is uncertain. The number of active Meliponini beekeepers is shy in comparison with the Africanized Apis mellifera breeders. The high honey yield, 100 kg (220 lbs) or more annually, along with the ease of hive care and ability to create new hives from existing stock, commonly outweighs the negative consequences of "killer bee" hive maintenance.[141]

An additional blow to the art of meliponine beekeeping is that many of the meliponicultores are now elderly, and their hives may not be cared for once they die. The hives are considered similar to an old family collection, to be parted out once the collector dies or to be buried in whole or part along with the beekeeper upon death. In fact, a survey of a once-popular area of the Maya lowlands shows the rapid decline of beekeepers, down to around 70 in 2004 from thousands in the late 1980s. Conservation efforts are underway in several parts of Mesoamerica.[141][142]

References

[edit]- ^ Grüter (2020, pp. 46–47)

- ^ a b c Nogueira (2023)

- ^ Michener (2000, p. 803)

- ^ Grüter (2020, p. 1)

- ^ Silveira (2002, p. 253)

- ^ Grüter (2020, p. 43)

- ^ Roubik (1989, p. 8)

- ^ Kajobe (2006)

- ^ a b Chakuya et al. (2022)

- ^ Michener (2000, p. 111)

- ^ Sarchet (2014)

- ^ Grüter (2020, pp. 7 & 16)

- ^ a b Grüter (2020, p. 65)

- ^ Grüter (2020, p. 4)

- ^ Grüter (2020, pp. 25–27)

- ^ Villas-Bôas (2018, pp. 14–15)

- ^ Michener (2000, p. 803)

- ^ a b c Grüter (2020, pp. 47–49)

- ^ Silveira (2002, p. 31)

- ^ Rasmussen, Thomas & Engel (2017)

- ^ Cortopassi-Laurino, Imperatriz-Fonseca & Roubik (2006)

- ^ Venturieri, Raiol & Pareira (2003)

- ^ Koch (2010)

- ^ Grüter (2020, pp. 28–29)

- ^ Souza et al. (2004)

- ^ a b Roubik (2023a)

- ^ Grüter (2020, pp. 54–56)

- ^ Rasmussen & Cameron (2009)

- ^ Jalil (2014, p. 126)

- ^ a b c Grüter (2020, pp. 43–44)

- ^ Payne (2014)

- ^ a b c d Grüter (2010, pp. 49–51)

- ^ Rasmussen & Cameron (2009)

- ^ Cardinal & Danforth (2011)

- ^ Cardinal & Danforth (2013)

- ^ Martins, Melo & Renner (2014)

- ^ a b Nogueira-Neto (1997, p. 78)

- ^ a b Nogueira-Neto (1997, p. 82)

- ^ Nogueira-Neto (1997, pp. 40–46)

- ^ Grüter (2020, pp. 12–15)

- ^ Grüter (2020, pp. 87–121)

- ^ Grüter (2020, pp. 7–11)

- ^ a b Villas-Bôas (2018, p. 23)

- ^ Nogueira-Neto (1997, pp. 82–83)

- ^ a b Villas-Bôas (2018, p. 19)

- ^ a b c Grüter (2020, pp. 7 & 5)

- ^ a b Imperatriz-Fonseca & Zucchi (1995)

- ^ Nogueira-Neto (1997, pp. 83–85)

- ^ Grüter (2020, p. 11)

- ^ Grüter (2020, p. 11)

- ^ Grüter et al. (2012)

- ^ Grüter et al. (2017)

- ^ Grüter (2020, p. 258)

- ^ Grüter (2020, pp. 17–24)

- ^ a b c d Nogueira-Neto (1997, pp. 40–46)

- ^ a b c d Grüter (2020, pp. 12–15)

- ^ a b c d Villas-Bôas (2018, pp. 24–26)

- ^ a b c d Venturieri (2004, pp. 23–30)

- ^ Mduda, Hussein & Muruke (2023)

- ^ Ferreira et al. (2009)

- ^ Sousa et al. (2016)

- ^ Mokaya et al. (2002)

- ^ a b c Fletcher et al. (2020a)

- ^ Layt, Stuart (2020-07-23). "Scientists say native stingless bee honey hits the sweet spot". Brisbane Times. Retrieved 2020-07-27.

- ^ Mduda, Hussein & Muruke (2023)

- ^ Rodríguez-Malaver et al. (2009)

- ^ Nweze et al. (2017)

- ^ Zulkhairi Amin et al. (2018)

- ^ a b c d e f Grüter (2020, pp. 87–97)

- ^ Venturieri (2004, pp. 36–39)

- ^ Contrera & Venturieri (2008)

- ^ a b Villanueva, Roubik & Colli-Ucán (1998)

- ^ Antonini & Martins (2003)

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Grüter (2020, pp. 102–109)

- ^ Villas-Bôas (2018, pp. 27–29)

- ^ a b c d Grüter (2020, p. 161)

- ^ a b c d Grüter (2020, pp. 131–152)

- ^ Engels (1987)

- ^ Nogueira-Neto (1997, pp. 367–390)

- ^ Embrapa. Inimigos Naturais & Cuidados Especiais. Curso Básico de Abelhas Sem Ferrão.

- ^ Villas-Bôas (2018, pp. 103–104)

- ^ Grüter (2020, pp. 235–236)

- ^ Nogueira-Neto (1997, pp. 368–370)

- ^ Grüter (2020, p. 236)

- ^ Villas-Bôas (2018, p. 106)

- ^ Grüter (2020, p. 235)

- ^ Villas-Bôas (2018, p. 105)

- ^ Grüter (2020, pp. 236–238)

- ^ a b Grüter (2020, pp. 238–239)

- ^ a b c Grüter (2020, pp. 248–260)

- ^ Ribeiro (2002)

- ^ Alves, Imperatriz-Fonseca & Santos-Filho (2009)

- ^ Roubik, Smith & Carlson (1987)

- ^ Roubik (2006)

- ^ Sarchet (2014)

- ^ Kerr (1950)

- ^ a b Wenseleers et al. (2005)

- ^ a b Michener (2000, pp. 4–5)

- ^ Ramalho (2004)

- ^ Brosi et al. (2008)

- ^ Cairns et al. (2005)

- ^ a b Grüter (2020, pp. 323–330)

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r Heard (1999)

- ^ Nunes-Silva et al. (2013)

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Slaa et al. (2006)

- ^ Azmi et al. (2019)

- ^ Putra, Salmah & Swasti (2017)

- ^ a b c d Kajobe (2008)

- ^ a b Byarugaba (2004)

- ^ a b c Eardley, Gikungu & Schwarz (2009)

- ^ Grüter (2010, pp. 47 & 49)

- ^ Grüter (2010, p. 27)

- ^ Wendy Pyper (May 8, 2003). "Stingless bee rescue". ABC Science.

- ^ Vit, Pedro & Roubik (2018)

- ^ "Australian Native Stingless Bees". www.aussiebee.com.au. Retrieved 2024-05-28.

- ^ Steve (2015-05-25). "Native Stingless Bees - Tetragonula carbonaria". www.nativebeehives.com. Retrieved 2024-05-28.

- ^ Thomas, Kerrin (2019-07-05). "Native bee honey set to have its own food standard". ABC News. Retrieved 2019-07-10.

- ^ "New Greenhouse Pollination Study With Trigona". Aussie Bee Bulletin (10). May 1999.

Pablo Occhiuzzi of the University of Western Sydney is studying the greenhouse pollination of capsicum with Trigona carbonaria.

- ^ Villas-Bôas (2018, p. 17)

- ^ CONAMA 2004 Resolution

- ^ "Arquivos Artigos - A.B.E.L.H.A." abelha.org.br (in Brazilian Portuguese). 2024-07-26. Retrieved 2024-12-31.

- ^ a b c d "Fichas catalográficas das espécies relevantes para a meliponicultura - A.B.E.L.H.A." abelha.org.br (in Brazilian Portuguese). 2022-02-21. Retrieved 2024-12-31.

- ^ "IBAMA". www.ibama.gov.br. Retrieved 2024-02-26.

- ^ ICMBio. 2018. Livro Vermelho da Fauna Brasileira Ameaçada de Extinção: Volume VII - Invertebrados. In: ICMBio. (Org.). Livro Vermelho da Fauna Brasileira Ameaçada de Extinção. Brasília: ICMBio. 727p.

- ^ Grüter (2010, p. 14)

- ^ Fonseca et al. (2007)

- ^ Grüter (2020, pp. 12–14)

- ^ João Luiz. "Meliponario Capixaba: É POSSÍVEL CRIAR ABELHAS EM APARTAMENTOS?". Retrieved 12 March 2016.

- ^ Brito et al. (1997)

- ^ "Lambe-olhos – Leurotrigona muelleri – Laboratório de Sistemática de Plantas". sites.usp.br. Retrieved 2024-12-31.

- ^ "Mirim – Plebeia droryana – Laboratório de Sistemática de Plantas". sites.usp.br. Retrieved 2024-12-31.

- ^ Castanheira & Contel (2005)

- ^ Kent (1984)

- ^ Grüter (2010, p. 54)

- ^ "Diccionario Introductorio" (PDF). uqroo.mx (in Spanish). Universidad De Quintana Roo. Retrieved 27 March 2014.

- ^ a b "People and bees. Mayan bees in the Madrid Codex". eComercio Agrario. 2016-07-17. Retrieved 2024-12-31.

- ^ a b Kennedy, Jennifer; Arghiris, Richard (2019-01-31). "House of the Royal Lady Bee: Maya revive native bees and ancient beekeeping". Mongabay Environmental News. Retrieved 2024-12-31.

- ^ Ott (1998)

- ^ Pitses (2018)

- ^ Schwarz (1945)

- ^ a b Villanueva-G, Roubik & Colli-Ucán (2005)

- ^ A comprehensive conservation guide can be found in the June 2005 issue of Bee World.

Bibliography

[edit]Articles and publications

[edit]- Alves, D A; Imperatriz-Fonseca, V L; Santos-Filho, P S. (2009). "Production of workers, queens and males in Plebeia remota colonies (Hymenoptera, Apidae, Meliponini), a stingless bee with reproductive diapause". Genetics and Molecular Research. 8 (2): 672–683. doi:10.4238/vol8-2kerr030. PMID 19554766.

- Antonini, Yasmine; Martins, Rogério P. (2003). "The value of a tree species (Caryocar brasiliense) for a stingless bee Melipona quadrifasciata quadrifasciata". Journal of Insect Conservation. 7 (3): 167–174. Bibcode:2003JICon...7..167A. doi:10.1023/A:1027378306119. S2CID 6080884.

- Azmi, Wahizatul Afzan; Wan Sembok, W Z; Yusuf, N; Mohd. Hatta, M F; Salleh, A F; Hamzah, M A H; Ramli, S N (2019-02-12). "Effects of Pollination by the Indo-Malaya Stingless Bee (Hymenoptera: Apidae) on the Quality of Greenhouse-Produced Rockmelon". Journal of Economic Entomology. 112 (1): 20–24. doi:10.1093/jee/toy290. ISSN 0022-0493. PMID 30277528.

- Byarugaba, Dominic (2004). "Stingless bees (Hymenoptera: Apidae) of Bwindi impenetrable forest, Uganda and Abayanda indigenous knowledge". International Journal of Tropical Insect Science. 24 (1): 117. Bibcode:2004IJTIS..24..117B. doi:10.1079/IJT20048. ISSN 1742-7584.

- Brito, B.B.P.; Faquinello, P.; Paula-Leite, M.C.; Carvalho, C.A.L. (2013). "Parâmetros biométricos e produtivos de colônias em gerações de Melipona quadrifasciata anthidioides". Archivos de Zootecnia. 62 (238): 265–273. doi:10.4321/S0004-05922013000200012. ISSN 0004-0592.

- Brosi, Berry J.; Daily, Gretchen C.; Shih, Tiffany M.; Oviedo, Federico; Durán, Guillermo (2008). "The effects of forest fragmentation on bee communities in tropical countryside". Journal of Applied Ecology. 45 (3): 773–783. Bibcode:2008JApEc..45..773B. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2664.2007.01412.x. ISSN 0021-8901.

- Cairns, Christine E.; Villanueva-Gutiérrez, Rogel; Koptur, Suzanne; Bray, David B. (2005). "Bee Populations, Forest Disturbance, and Africanization in Mexico 1". Biotropica. 37 (4): 686–692. Bibcode:2005Biotr..37..686C. doi:10.1111/j.1744-7429.2005.00087.x. ISSN 0006-3606. S2CID 55048328.

- Campbell, Alistair John; Carvalheiro, Luísa Gigante; Maués, Marcia Motta; Jaffé, Rodolfo; Giannini, Tereza Cristina; Freitas, Madson Antonio Benjamin; Coelho, Beatriz Woiski Texeira; Menezes, Cristiano (2018). Magrach, Ainhoa (ed.). "Anthropogenic disturbance of tropical forests threatens pollination services to açaí palm in the Amazon river delta". Journal of Applied Ecology. 55 (4): 1725–1736. Bibcode:2018JApEc..55.1725C. doi:10.1111/1365-2664.13086. ISSN 0021-8901.

- Cardinal, Sophie; Danforth, Bryan N. (2011-06-13). "The Antiquity and Evolutionary History of Social Behavior in Bees". PLOS ONE. 6 (6): e21086. Bibcode:2011PLoSO...621086C. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0021086. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 3113908. PMID 21695157.

- Cardinal, Sophie; Danforth, Bryan N. (2013-03-22). "Bees diversified in the age of eudicots". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 280 (1755): 20122686. doi:10.1098/rspb.2012.2686. ISSN 0962-8452. PMC 3574388. PMID 23363629.

- Castanheira, Eliana Barroso; Contel, Eucleia Primo Betioli (2005-01-01). "Geographic variation in Tetragonisca angustula (Hymenoptera, Apidae, Meliponinae)". Journal of Apicultural Research. 44 (3): 101–105. Bibcode:2005JApiR..44..101C. doi:10.1080/00218839.2005.11101157. ISSN 0021-8839.

- Chakuya, Jeremiah; Gandiwa, Edson; Muboko, Never; Muposhi, Victor K. (2022-05-03). "A Review of Habitat and Distribution of Common Stingless Bees and Honeybees Species in African Savanna Ecosystems". Tropical Conservation Science. 15: 194008292210996. doi:10.1177/19400829221099623. ISSN 1940-0829. S2CID 248585511.

- Contrera, F A L; Venturieri, G C. (2008). "Vantagens e Limitações do Uso de Abrigos Individuais e Comunitários para a Abelha Indígena sem Ferrão Uruçu-Amarela (Melipona flavolineata)"" (PDF). Comunicado Técnico Embrapa Amazônia Oriental. 211: 1–6.

- Cortopassi-Laurino, M C; Imperatriz-Fonseca, V L; Roubik, D W; et al. (2006). "Global meliponiculture: challenges and opportunities". Apidologie. 37 (2): 275–292. doi:10.1051/apido:2006027.

- Eardley, Connal D.; Gikungu, Mary; Schwarz, Michael P. (2009). "Bee conservation in Sub-Saharan Africa and Madagascar: diversity, status and threats". Apidologie. 40 (3): 355–366. doi:10.1051/apido/2009016. ISSN 0044-8435.

- Engels, Wolf (1987). "Pheromones and reproduction in brazilian stingless bees". Memórias do Instituto Oswaldo Cruz. 82: 35–45. doi:10.1590/S0074-02761987000700009. ISSN 0074-0276.

- Ferreira, E.L.; Lencioni, C.; Benassi, M.T.; Barth, M.O.; Bastos, D.H.M. (2009-07-30). "Descriptive Sensory Analysis and Acceptance of Stingless Bee Honey". Food Science and Technology International. 15 (3): 251–258. doi:10.1177/1082013209341136. ISSN 1082-0132. S2CID 84700846.

- Fletcher, Mary T.; Hungerford, Natasha L.; Webber, Dennis; Carpinelli de Jesus, Matheus; Zhang, Jiali; Stone, Isobella S. J.; Blanchfield, Joanne T.; Zawawi, Norhasnida (2020-07-22). "Stingless bee honey, a novel source of trehalulose: a biologically active disaccharide with health benefits". Scientific Reports. 10 (1): 12128. Bibcode:2020NatSR..1012128F. doi:10.1038/s41598-020-68940-0. ISSN 2045-2322. PMC 7376065. PMID 32699353.

- Fonseca, Antônio Augusto O.; Sodré, Geni da Silva; Carvalho, Carlos Alfredo L. de; Alves, Rogério Marcos de O.; Souza, Bruno de Almeida; Silva, Samira Maria P. C. da; Oliveira, Gabriela Andrade de; Machado, Cerilene S.; Clarton, Lana (2006). "Qualidade do Mel de Abelhas sem Ferrão: uma proposta para boas práticas de fabricação" (PDF). Série Meliponicultura (5): 79.

- Giannini, T. C.; Boff, S.; Cordeiro, G. D.; Cartolano, E. A.; Veiga, A. K.; Imperatriz-Fonseca, V. L.; Saraiva, A. M. (2015-03-01). "Crop pollinators in Brazil: a review of reported interactions". Apidologie. 46 (2): 209–223. doi:10.1007/s13592-014-0316-z. ISSN 1297-9678. S2CID 256200439.

- Grüter, Christoph; Menezes, Cristiano; Imperatriz-Fonseca, Vera L.; Ratnieks, Francis L. W. (2012-01-24). "A morphologically specialized soldier caste improves colony defense in a neotropical eusocial bee". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 109 (4): 1182–1186. doi:10.1073/pnas.1113398109. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 3268333. PMID 22232688.

- Grüter, Christoph; Segers, Francisca H. I. D; Menezes, Cristiano; Vollet-Neto, Ayrton; Falcón, Tiago; von Zuben, Lucas; Bitondi, Márcia M. G; Nascimento, Fabio S; Almeida, Eduardo A. B (2017). "Repeated evolution of soldier sub-castes suggests parasitism drives social complexity in stingless bees". Nature Communications. 8 (1): 4. Bibcode:2017NatCo...8....4G. doi:10.1038/s41467-016-0012-y. PMC 5431902. PMID 28232746.

- Heard, Tim A. (1999). "The role of stingless bees in crop pollination". Annual Review of Entomology. 44 (1): 183–206. doi:10.1146/annurev.ento.44.1.183. ISSN 0066-4170. PMID 15012371.

- Imperatriz-Fonseca, V. L.; Zucchi, R. (1995). "Virgin queens in stingless bee (Apidae, Meliponinae) colonies: a review". Apidologie. 26 (3): 231–244. doi:10.1051/apido:19950305. ISSN 0044-8435.

- Kajobe, Robert (2006-12-12). "Nesting biology of equatorial Afrotropical stingless bees (Apidae; Meliponini) in Bwindi Impenetrable National Park, Uganda". Journal of Apicultural Research. 46 (4): 245–255. doi:10.1080/00218839.2007.11101403. ISSN 0021-8839. S2CID 84923320.

- Kent, Robert B. (1984). "Mesoamerican Stingless Beekeeping". Journal of Cultural Geography. 4 (2): 14–28. doi:10.1080/08873638409478571. ISSN 0887-3631.

- Kerr, W E. (1950). "Genetic determination of castes in the genus Melipona". Genetics. 35 (2): 143–152. doi:10.1093/genetics/35.2.143. PMC 1209477. PMID 17247339.

- Kerr, Warwick Estevam; Petrere Jr., Miguel; Diniz Filho, José Alexandre Felizola (March 2001). "Informações biológicas e estimativa do tamanho ideal da colmeia para a abelha tiúba do Maranhão (Melipona compressipes fasciculata Smith - Hymenoptera, Apidae)". Revista Brasileira de Zoologia (in Portuguese). 18: 45–52. doi:10.1590/S0101-81752001000100003. hdl:11449/28338. ISSN 0101-8175.

- Koch, H. (2010). "Combining morphology and DNA barcoding resolves the taxonomy of Western Malagasy Liotrigona Moure", 1961". African Invertebrates. 51 (2): 413–421. doi:10.5733/afin.051.0210. S2CID 49266406. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-09-12.

- Martins, Aline C.; Melo, Gabriel A. R.; Renner, Susanne S. (2014-11-01). "The corbiculate bees arose from New World oil-collecting bees: Implications for the origin of pollen baskets". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 80: 88–94. Bibcode:2014MolPE..80...88M. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2014.07.003. ISSN 1055-7903. PMID 25034728.

- Mduda, Christopher Alphonce; Hussein, Juma Mahmud; Muruke, Masoud Hadi (2023-12-01). "The effects of bee species and vegetation on the antioxidant properties of honeys produced by Afrotropical stingless bees (Hymenoptera, Apidae, Meliponini)". Journal of Agriculture and Food Research. 14: 100736. doi:10.1016/j.jafr.2023.100736. ISSN 2666-1543. S2CID 260829534.

- Mokaya, Hosea O.; Nkoba, Kiatoko; Ndunda, Robert M.; Vereecken, Nicolas J. (2022-01-01). "Characterization of honeys produced by sympatric species of Afrotropical stingless bees (Hymenoptera, Meliponini)". Food Chemistry. 366: 130597. doi:10.1016/j.foodchem.2021.130597. ISSN 0308-8146. PMID 34314935.

- Mrema, Ida A.; Nyundo, Bruno A. (2016-02-29). "Pollinators of Allanblackia stuhlmannii (Engl.), Mkani fat an endemic tree in eastern usambara mountains, Tanzania". International Journal of Pure & Applied Bioscience. 4 (1): 61–67. doi:10.18782/2320-7051.2203.

- Nogueira, David Silva (2023-08-02). "Overview of Stingless Bees in Brazil (Hymenoptera: Apidae: Meliponini)". EntomoBrasilis. 16: e1041. doi:10.12741/ebrasilis.v16.e1041. ISSN 1983-0572. Retrieved 2023-12-07.

- Nunes-Silva, Patrícia; Hrncir, Michael; da Silva, Cláudia Inês; Roldão, Yara Sbrolin; Imperatriz-Fonseca, Vera Lucia (2013-09-01). "Stingless bees, Melipona fasciculata, as efficient pollinators of eggplant (Solanum melongena) in greenhouses". Apidologie. 44 (5): 537–546. doi:10.1007/s13592-013-0204-y. ISSN 1297-9678. S2CID 256206288.

- Nweze, Justus Amuche; Okafor, J. I.; Nweze, Emeka I.; Nweze, Julius Eyiuche (2017-11-06). "Evaluation of physicochemical and antioxidant properties of two stingless bee honeys: a comparison with Apis mellifera honey from Nsukka, Nigeria". BMC Research Notes. 10 (1): 566. doi:10.1186/s13104-017-2884-2. ISSN 1756-0500. PMC 5674770. PMID 29110688.

- Ott, Jonathan (1998). "The Delphic bee: Bees and toxic honeys as pointers to psychoactive and other medicinal plants". Economic Botany. 52 (3): 260–266. Bibcode:1998EcBot..52..260O. doi:10.1007/BF02862143. S2CID 7263481.

- Payne, Ansel (2014). "Resolving the relationships of apid bees (Hymenoptera: Apidae) through a direct optimization sensitivity analysis of molecular, morphological, and behavioural characters". Cladistics. 30 (1): 11–25. doi:10.1111/cla.12022. ISSN 0748-3007. PMID 34781592.

- Putra, Dewirman Prima; Dahelmi; Salmah, Siti; Swasti, Etti (2017). "Daily Flight Activity of Trigona laeviceps and T. minangkabau in Red Pepper (Capsicum annuum L.) Plantations in Low and High Lands of West Sumatra". International Journal of Applied Environmental Sciences. 12 (8): 1497–1507. ISSN 0973-6077.

- Ramalho, Mauro (2004). "Stingless bees and mass flowering trees in the canopy of Atlantic Forest: a tight relationship". Acta Botanica Brasilica. 18: 37–47. doi:10.1590/S0102-33062004000100005. ISSN 0102-3306.

- Rasmussen, Claus (2013-05-10). "Stingless bees (Hymenoptera: Apidae: Meliponini) of the Indian subcontinent: Diversity, taxonomy and current status of knowledge". Zootaxa. 3647 (3): 401–428. doi:10.11646/zootaxa.3647.3.1. ISSN 1175-5334. PMID 26295116.

- Rasmussen, Claus; Cameron, Sydney A. (2009-12-18). "Global stingless bee phylogeny supports ancient divergence, vicariance, and long distance dispersal: STINGLESS BEE PHYLOGENY". Biological Journal of the Linnean Society. 99 (1): 206–232. doi:10.1111/j.1095-8312.2009.01341.x.

- Rasmussen, Claus; Thomas, Jennifer C; Engel, Michael S (2017). "A New Genus of Eastern Hemisphere Stingless Bees (Hymenoptera: Apidae), with a Key to the Supraspecific Groups of Indomalayan and Australasian Meliponini" (PDF). American Museum Novitates (3888): 1–33. doi:10.1206/3888.1. hdl:2246/6817. S2CID 89696073.

- Ribeiro, M F. (2002). "Does the queen of Plebeia remota ( Hymenoptera , Apidae , Meliponini ) stimulate her workers to start brood cell construction after winter?". Insectes Sociaux. 49: 38–40. doi:10.1007/s00040-002-8276-0. S2CID 21516827.

- Rodríguez-Malaver, Antonio J.; Rasmussen, Claus; Gutiérrez, María G.; Gil, Florimar; Nieves, Beatriz; Vit, Patricia (2009-09-01). "Properties of Honey from Ten species of Peruvian Stingless Bees". Natural Product Communications. 4 (9): 1934578X0900400. doi:10.1177/1934578X0900400913. ISSN 1934-578X. S2CID 27049265.

- Roubik, David W. (2023-01-23). "Stingless Bee (Apidae: Apinae: Meliponini) Ecology". Annual Review of Entomology. 68 (1): 231–256. doi:10.1146/annurev-ento-120120-103938. ISSN 0066-4170. PMID 36198402.

- Roubik, D. W; Smith, B. H; Carlson, R. G (1987). "Formic acid in caustic cephalic secretions of stingless bee, Oxytrigona (Hymenoptera: Apidae)". Journal of Chemical Ecology. 13 (5): 1079–86. Bibcode:1987JCEco..13.1079R. doi:10.1007/BF01020539. PMID 24302133. S2CID 30511107.

- Roubik, D W. (2006). "Stingless bee nesting biology". Apidologie. 37 (2): 124–143. doi:10.1051/apido:2006026.

- Sarchet, Penny (14 November 2014). "Zoologger: Stingless suicidal bees bite until they die". New Scientist. Retrieved 2020-01-24.

- Schwarz, Herbert F. (1945). "The Wax of Stingless Bees (Meliponidæ) and the Uses to Which It Has Been Put". Journal of the New York Entomological Society. 53 (2): 137–144. ISSN 0028-7199. JSTOR 25005104.

- Slaa, Ester Judith; Chaves, Luis Alejandro Sánchez; Malagodi-Braga, Katia Sampaio; Hofstede, Frouke Elisabeth (2006-03-01). "Stingless bees in applied pollination: practice and perspectives". Apidologie. 37 (2): 293–315. doi:10.1051/apido:2006022. hdl:11056/27850. ISSN 0044-8435. S2CID 55280074.

- Sousa, Janaína Maria Batista de; Souza, Evandro Leite de; Marques, Gilmardes; Benassi, Marta de Toledo; Gullón, Beatriz; Pintado, Maria Manuela; Magnani, Marciane (2016-01-01). "Sugar profile, physicochemical and sensory aspects of monofloral honeys produced by different stingless bee species in Brazilian semi-arid region". LWT - Food Science and Technology. 65: 645–651. doi:10.1016/j.lwt.2015.08.058. ISSN 0023-6438.

- Souza, R C S; Yuyama, L K O; Aguiar, J P L; Oliveira, F P M. (2004). "Valor nutricional do mel e pólen de abelhas sem ferrão da região amazônica". Acta Amazonica. 34 (2): 333–336. doi:10.1590/s0044-59672004000200021.

- Venturieri, G C; Raiol, V F O; Pareira, C A B (2003). "Avaliação da introfução da criação racional de Melipona fasciculata (Apidae: Meliponina), entre os agricultores familiares de Bragança - PA, Brasil". Biota Neotropica. 3 (2): 1–7. doi:10.1590/s1676-06032003000200003.

- Viana, Blandina Felipe; Coutinho, Jeferson Gabriel da Encarnação; Garibaldi, Lucas Alejandro; Castagnino, Guido Laercio Bragança; Gramacho, Kátia Peres; Silva, Fabiana Oliveira (2014-10-09). "Stingless bees further improve apple pollination and production". Journal of Pollination Ecology. 14: 261–269. doi:10.26786/1920-7603(2014)26. ISSN 1920-7603.

- Villanueva, Rogel; et al. (2005). "Extinction of Melipona beecheii and traditional beekeeping in the Yucatán peninsula". Bee World. 86 (2): 35–41. doi:10.1080/0005772X.2005.11099651. S2CID 31943555.